'WITH VOICE, PEN, MONEY, OR OTHERWISE'

Tracking Women's Involvement in Spiritualist Print Culture

in 19th Century California

How did women and women's labor shape the life cycles of Spiritualist printed texts in California?

“In addition to many noble workers native to it or resident therein, this coast has been enriched by the presence and labors of a number of the leading ‘workers in the vineyard’ from all parts of America, and from England and other countries…the mediums, the lecturers, the writers, the workers in the societies and the lyceums, the sustainers and promoters of the good work by their means, their time, their influence, etc.,—the active ‘workers’ in the cause, whether with voice, pen, money, or otherwise.” [1]

-- Wm. Emmette Coleman, in Julia Schlesinger’s Workers in the Vineyard (1896)

This site tracks my research investigating the women who were among these active workers in California from approximately 1850-1900. Women were an important part of the collaborative creation of Spiritualist texts. While print production was still a male-dominated space, women were enmeshed in Spiritualist print culture and helped connect communities across the West Coast and across the country through the printed word.

Explore the site using the tabs above. Their World provides context for the time and place. The Women's Network is the home base for navigating the different categories of women's labor, or you can use its dropdown menu. And keep an eye out for resource links -- when a primary source is freely digitized online, I've tried to provide a direct hyperlink.

For more details on this project’s model and its relationship to existing scholarship, continue scrolling below.

The Women's Network

This network demonstrates Helen Smith’s “spiderweb” model of women in book history, which she outlines in 'Grossly Material Things': Women and Book Production In Early Modern England (2012)[2]. Smith does a feminist revision of Robert Darnton’s oft-cited “Communications Circuit,” which sought to diagram “a circuit for transmitting texts” with an emphasis on people rather than only objects [3]. Darnton’s circuit is a valuable model for visualizing people’s roles in print production, but Smith rightfully critiques the traditional depiction of book history as a solely male realm. Drawing from Virginia Woolf’s description in A Room of One’s Own of fiction as a spider’s web, with each interconnected thread holding up a corner of “grossly material things”[4], Smith argues that printed texts are products of complex, embodied, and laborious social factors:

“Rather than being a circuit or map, the life of a book may best be represented through Woolf’s web, connecting the discursive strands of the text to the people and things which shape and are shaped by it…the strands of the web are not simply dependent upon, but are made of, interlinked economic, social, and corporeal relationship.” [5]

I draw inspiration from Smith’s spiderweb to envision the vibrant culture of Spiritualist texts in California, and I've chosen to focus on identifying the roles that women inhabited. This project does not encompass all the factors at play in the web — but showing the relationships between people and highlighting individual women’s labor helps illuminate at least part of this printed world.

Literature Review

Investigating women’s involvement in the Spiritualist print industry can open new avenues to understanding women’s vital contributions to American religious history and our modern media culture. Ever since Anne Braude’s foundational Radical Spirits (1989), which argued for the compatibility of nineteenth-century Spiritualism and women’s rights, historians have been expanding the picture of Spiritualism’s impact on American social life [6]. Braude’s research was a much-needed intervention in how scholars usually depicted Spiritualism as a fringe movement that attracted gullible people, especially women, who believed fantastical claims. Rather, Spiritualism gained widespread belief and curiosity, and often attracted political radicals and social reformers.

Many authors in the last few decades have written about Spiritualism—you can find a starting list on the Suggested Resources page. But scholars have paid relatively less attention to women’s involvement in the Spiritualist publishing industry, and even less on its West Coast presence (with a few exceptions). Furthermore, the Spiritualism of Black women has begun to receive more consideration [7], but much work remains to fully integrate African American and BIPOC experiences in our histories on Spiritualism and West Coast print culture.

There are numerous works on 19th century printing in the United States, and several on Spiritualist printing in particular, like its dynamics of mediumship and authorship [8]. Dianne Roman has researched women in 19th century letterpress printing [9]. Roger Levenson’s standout work Women in Printing: Northern California, 1857-1890 (1994) compiles detailed research on women master-printers, typesetters, and newspaper editors, a number of which were Spiritualists [10]. Much of my material on women in these roles is indebted to his legwork.

In the spirit of Braude’s call to take Spiritualist women more seriously, and of Helen Smith’s call to question a supposedly all-male book history, this project seeks to identify women’s important presence in Spiritualist print in California and thus contribute to a more complete understanding of life in 19th century America.

About Me

Hi! I’m Erin Wiebe, an archivist and historian. I’m thrilled to be continuing my research on Spiritualist women and print, and learning more about how religious women shared their ideas of radical new worlds through words, texts, and embodiment.

Have a comment, question, correction, or research lead on women and Spiritualist texts in California?

Use the form below to get in touch!

Sources

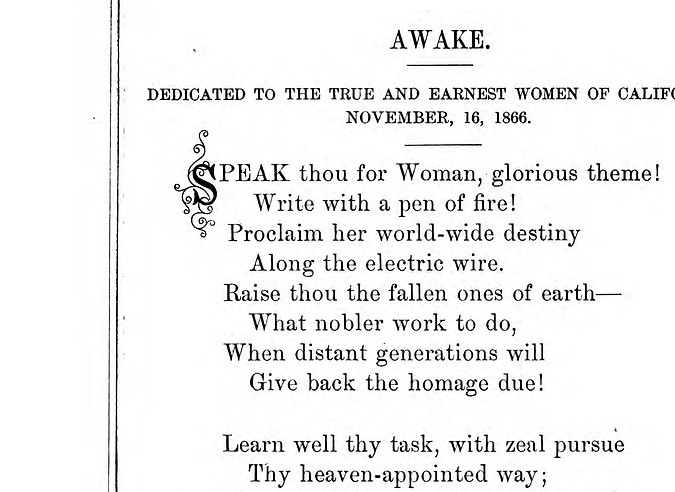

[Image] Detail from Mrs. E. P. Thorndyke, Astrea, Or Goddess of Justice (San Francisco: Amanda M. Slocum, 1881), page 48, HathiTrust Digital Library, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007092308.

[1] Wm. Emmette Coleman, “Introduction,” in Workers in the Vineyard: A Review of the Progress of Spiritualism, Biographical Sketches, Lectures, Essays and Poems, by Julia Schlesinger (San Francisco, California, 1896), 16, HathiTrust Digital Library, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100128052.

[2] Helen Smith, “Introduction,” in ’Grossly Material Things': Women and Book Production In Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 1-15, e-book, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.32872, accessed 24 Jan 2021, downloaded on behalf of Wellesley College.

[3] Robert Darnton, “What is the history of books?” Daedalus 111, no. 3 (1982): 67, Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard. Darnton also revised his Communications Circuit in a later article: Robert Darnton, “‘What is the history of books?’ Revisited,” Modern Intellectual History 4, no. 3 (2007): 495–508, doi:10.1017/S1479244307001370, Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard.

[4] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (London: Hogarth Press, 1935), 62-63, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/woolf_aroom/page/n1/mode/2up.

[5] Helen Smith, “Introduction,” 9-10.

[6] Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America, 2nd ed. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2001).

[7] See Margaret Washington, Sojourner Truth’s America (University of Illinois Press, 2009); Mary Ann Clark, “Spirit Is Universal: Development of Black Spiritualist Churches,” in Esotericism in African American Religious Experience: ‘There Is a Mystery’…, ed. Stephen Finley, Margarita Guillory, and Hugh R. Page, Jr. (Leiden: BRILL, 2014), 86-101; R. J. Ellis and Henry Louis Gates, “‘Grievances at the Treatment She Received’: Harriet E. Wilson's Spiritualist Career in Boston, 1868—1900,” American Literary History 24, no. 2 (2012): 234-64; and Erin E. Forbes, “Do Black Ghosts Matter?: Harriet Jacobs’ Spiritualism,” ESQ: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture 62, no. 3 (2016): 443–79.

[8] For example, see Simone Natale, Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of the Modern Media Culture (Penn State University Press, 2016); and E. Haven Hawley, “William Berry: Publisher, Scoundrel, and Spiritualist,” Printing History 22 (Summer 2017): 30–52.

[9] Dianne Roman, “Women at the Crossroads, Women at the Forefront, American Women in Letterpress Printing In the Nineteenth Century," PhD diss., (Virginia Commonwealth University, 2016). https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4595/.

[10] Roger Levenson, Women in Printing: Northern California, 1857-1890 (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1994).